Posted March 20, 2017

Last modified March 20, 2017

A survey aimed at residents of Maine’s 15 unbridged, year-round island communities reveals deep concern about ticks and the diseases they carry, such as Lyme disease.

The survey found that 83 percent of those responding “thought Lyme disease was a problem on their island,” a March 3 preliminary report on the survey noted. “The opinion that Lyme disease was a problem was consistently high,” the summary further noted, “and did not differ by age, gender, education or year-round vs. seasonal residency.”

Fifty-seven percent of respondents had contracted a tick-borne illness or had a family member who had been infected. And of those, 78 percent were island-acquired.

Concern about Lyme and other diseases on islands is well-founded.

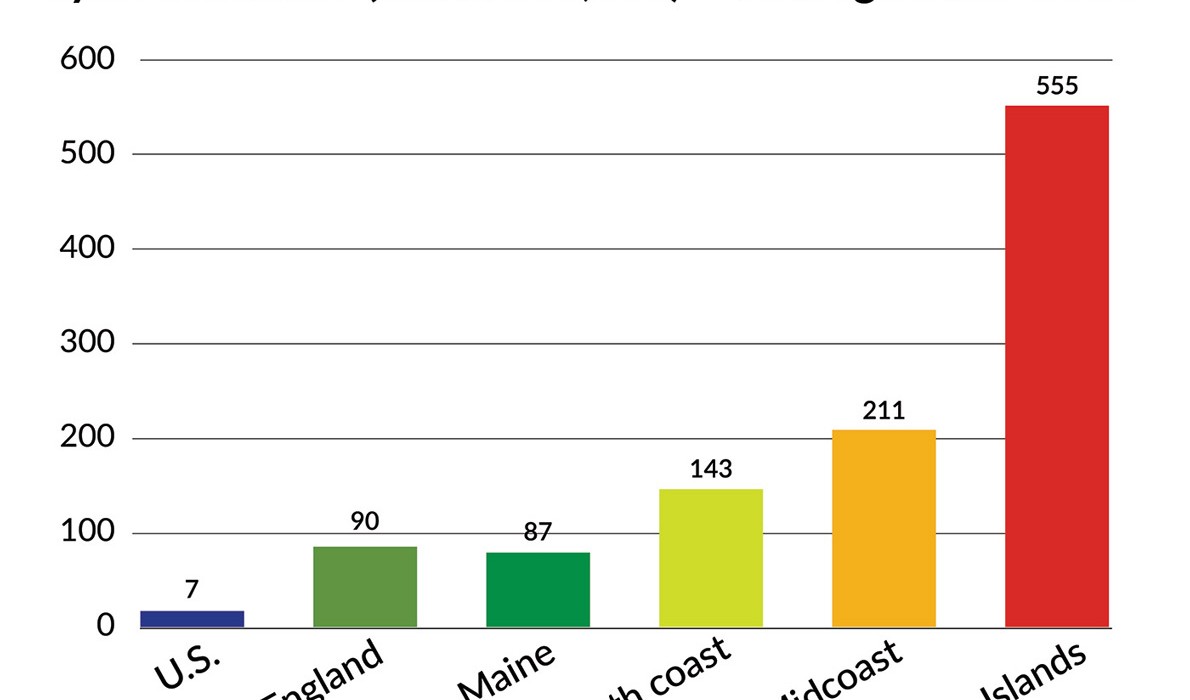

“It is clear that Lyme incidence on islands is exceptionally high, averaging 555 cases per 100,000 population” for the period from 2010 to 2014, the report noted. That compares with Maine’s statewide rate of 87 cases per 100,000 population, and New England’s rate of 90 per 100,000.

The survey, conducted by the Maine Medical Center Vector-borne Disease Lab, was not a random sampling, staff point out, but rather “an open invitation for islanders to express their experiences and opinions about ticks and tick control,” a summary of the results explained.

The survey opened on May 16 last year, and remained available online through the end of the year. Written responses are still being entered, Susan Elias, a research associate with the lab reported, but 772 responses were logged. Those included year-round (54 percent) and seasonal (46 percent) islanders. Almost all the seasonal islander respondents stay on-island for a month or more.

Seventy percent of respondents were women, which was not a surprise, the report notes, because in the U.S., “women tend to be the managers of health care in their households.”

A tick count, using light colored cloth, underway: the cloth is tossed onto ground cover and then dragged; staff then count the ticks that have attached.

The survey also sought to gauge islander attitudes about tick management strategies.

The report noted that 96 percent of respondents used the personal tick check after possible exposure.

“While all preventive measures are important, we think the tick check is the most important,” the report noted.

A key question in the survey addressed the increase in deer tick numbers, with four possible answers offered to respondents: climate change, white-tail deer overabundance, rodents and invasive species. Deer overpopulation was the most frequently cited cause (79 percent), followed by rodents (62 percent), climate change (47 percent) and invasive plants (27 percent).

The survey also asked about the four factors in combination.

“This is of great interest because the ecology of infectious diseases entails looking at the entire landscape to understand how all the pieces of the ecological puzzle fall into place.”

Eighty-two percent said deer were a problem on islands, both for their association with Lyme and because the damage they do in yards. Given that, Elias was surprised, she wrote, that just 61 percent believe there is a need to reduce the deer population.

“Only on Islesboro were seasonal residents more likely to favor deer reduction (90 percent) than year-round residents (47 percent),” she wrote.

The preliminary report concluded:

“It is our sense that a suite of factors (including climate change and deer, white-footed mouse, and invasive plants) have a role in the increase in deer ticks… Specifically, deer and mice may be locally overabundant. We also know that dense thickets of invasive plant species like Japanese barberry are great habitats for deer ticks and mice. Meanwhile, a trend of warmer winters is likely improving tick survival.”

Contributed by