Posted July 10, 2019

Last modified July 10, 2019

By Tom Groening

It was one of the more absurd exchanges the Jerry and George characters have on the TV show Seinfeld, which is saying something. The topic was explorers. Jerry extols the achievements of Magellan.

“Oh yeah, my favorite explorer. Around the world? Come on,” he says. “Why, who do you like?”

George endorses De Soto, which prompts Jerry to ask why.

“He discovered the Mississippi,” George exclaims.

To which Jerry replies, “Oh, like they wouldn't have found it anyway.”

If I’d been at the coffee shop, I would have waved the flag for Samuel de Champlain. He put his stamp on our corner of the world, even though the French flag he sailed under no longer flies over much of it.

A few years ago, I read a dense academic biography of the man, and my admiration for him grew.

Historians suspect Champlain, born in the middle-1500s into a modest family, actually was an illegitimate son of French monarch Henri IV—apparently, he had dozens—as evidenced by the ease with which he gained access to the king and his court. Champlain’s bids to join voyages to the New World also won easy favor with those in power.

Regardless of his pedigree, the way Champlain conducted himself in our region endears him to us, even in the current climate in which Maine, for example, has ditched Columbus Day in favor of Indigenous Peoples Day.

Like other European explorers, Champlain aimed at colonizing the region. So there is that. But his interactions with native peoples were notably better than that of other explorers.

Champlain saw them as partners in his ventures, and, by available accounts, treated them with dignity and respect. His settlements were fortified from fears of attack by the English, not the native inhabitants.

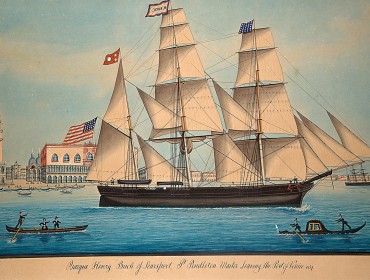

Champlain’s first foray into the Northeast came in 1603 and brought him up into the St. Lawrence River all the way to present day Montreal. As a lead explorer the following year, he established a colony on a small island on the St. Croix River just south of Calais, today an international historic site.

It was a miserable year for the settlers, as the island was locked in by ice, and then in spring, they suffered with blackflies and mosquitos. Scurvy and other illnesses killed almost half the group.

They decamped to the Annapolis Basin area of Nova Scotia for the following two years, but Champlain continued to scout the region for a better location. He visited Nauset Harbor on Cape Cod, and described the sandy hills there rimmed with native villages, a sharp contrast to what was seen by the English settlers of the Plymouth Colony some 15 years later; that decimation was likely the result of disease.

Champlain’s greatest success came in establishing Quebec in 1608. And his greatest impact may have been his writings. He published seven books in all, describing his explorations, and he avoided the hyperbole that characterized much of the era’s exploration literature.

Those partnerships with the native peoples included a military campaign with the northern tribes against the Iroquois, which brought him to the lake that now bears his name on the Vermont-New York border. Champlain writes of his shock at seeing captured warriors tortured at the hands of his allied tribes, observing that the native women of his group were the cruelest.

The explorer did not impose his Christian beliefs on native people, as he perhaps recalled the horrors of the religious wars that ravaged late 16thcentury France.

Champlain does recount the sexual culture of the native people, which saw young adults walking around the camp at night and, as would be said today, “hooking up.” One especially attractive young native woman propositioned the Frenchman, who may have been outside for a “call of nature,” and he turned her down, telling her to return to her tent. The news of his restraint led to a higher regard among the people as the story was shared.

Champlain also writes of a gathering with natives in a grove of oaks in present-day Bangor, as he and his party sat around a fire, smoking with the natives. I suspect that site is where the city’s Oak Street is today.

So yes, New England and the Atlantic provinces would have been “found” anyway, but we can be proud of “our” explorer.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront.

Contributed by