Stonington, the state of Maine’s top fishing port in landed value, is facing seismic change. By mid-century, its lobster fishery could drop by 15 to 20 percent due to warming ocean waters, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute predicts.

Tethered to the mainland by a thin thread of causeway and an 80-year-old bridge, this small town also faces rising seas that threaten infrastructure — including the town pier and a waterfront fire station.

Kathleen Billings, Stonington’s town manager, knows that “worse stuff is coming.” Seven years ago, she began reviewing inundation maps, writing grants to assess the vulnerability of town infrastructure and setting aside funds.

“All these projects are really daunting, and you can’t just keep putting your mil rate up,” she says. “We’re maxed now as is.”

Stonington has received state funds for planning and design, notes its economic development specialist Henry Teverow, but not for “physical infrastructure improvements. That’s where we need help the most.”

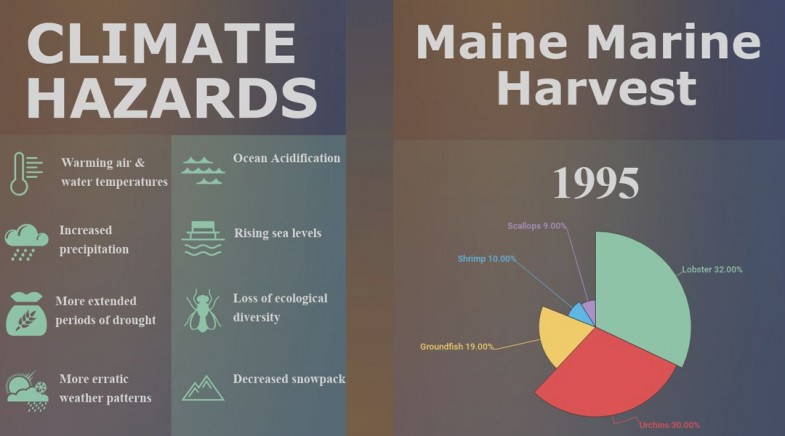

Climate hazards in Maine are placing an increasing strain on state and municipal budgets — reducing revenues, raising expenses and causing some economic shocks (such as price spikes in materials and food due to disruptions elsewhere). Yet little effort is being made to quantify the potential impacts.