Posted May 19, 2015

Last modified May 19, 2015

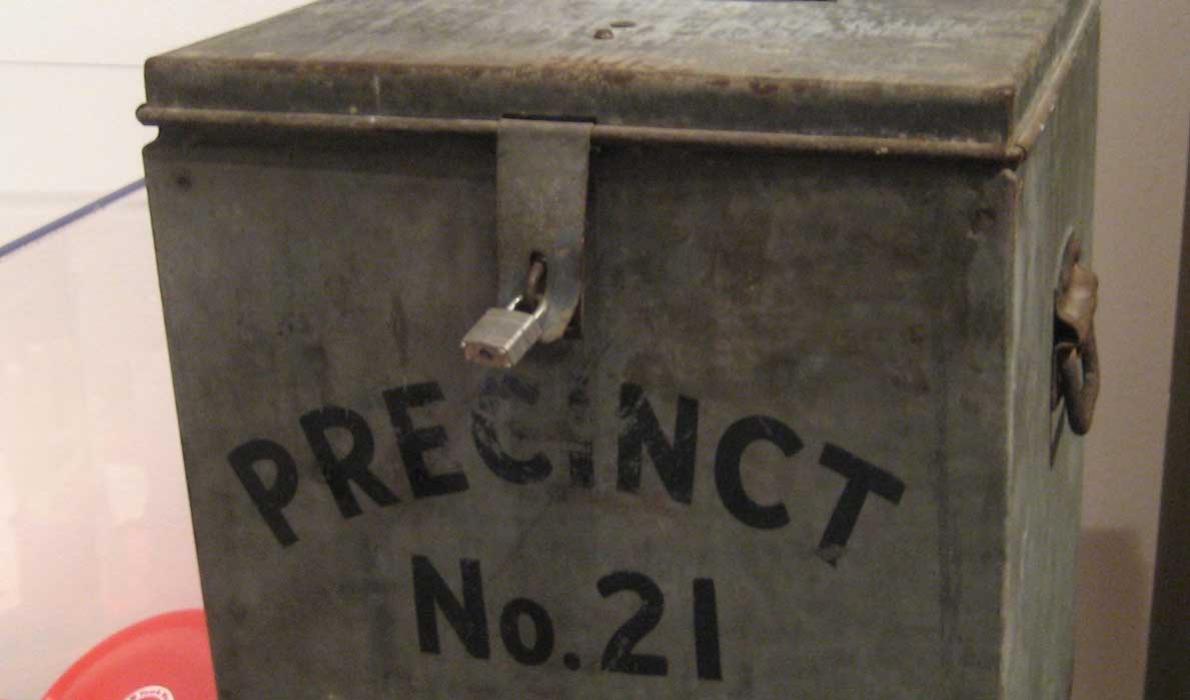

The traditional March town meeting in Maine, an institution that has launched many a laudatory newspaper editorial praising it as the last bastion of pure democracy, ain't what it used to be. And that's too bad.

In recent decades, management of schools, law enforcement, solid waste and other government functions have become regional. With the fixed bill of education typically eating up half or more of the property tax bill, the spending decisions made at town meeting have less impact on those casting their ballots. Much of the warrant is pro forma; after all, is anyone really going to vote against the snow-plowing budget?

And the meetings themselves have been moved out of the traditional month of March, for a variety of reasons; some budget years now start on July 1, so May makes more sense for the meeting, and the vagaries of March weather can interfere with attendance.

But there are moments in our communities here on the coast and islands when we local yokels get to have our say on big questions. As fired up as folks get about presidential elections, their votes carry so much more weight in these local initiatives. As is appropriate, votes on town matters generate just as much passion and vociferous rhetoric as does the question of whether a donkey or elephant will move into the White House.

In St. George, the town that sprawls across a peninsula south of Rockland and includes the lovely waterfront villages of St. George, Tenants Harbor, Martinsville, parts of Spruce Head and Port Clyde, voters approved the $810,000 purchase of a pier, land and building in Port Clyde. Though it was a big-ticket item, the vote wasn't even close—245-104.

Residents see the value in such a long-term investment, especially in a community so intimately aware of the importance of working waterfront infrastructure.

St. George also includes scenery as picturesque as anything in coastal Maine; it is, quite literally, the backdrop of the Wyeth version of Maine people all over the world picture when they think of us. And this is another reason why voters were wise to buy the property in Port Clyde. Our visitors want to be able to walk to a place they can see lobster boats returning from a day of hauling, smell the sea and take in the view. Trophy houses with high fences or a hotel with vigilant security could have been in Port Clyde's future, if not for the purchase.

Up the coast a bit in the island town of Islesboro, voters at their town meeting on May 30 (rescheduled from May 9) will consider another big investment. A town committee has researched and the select board endorsed a plan to build a broadband network on the island, to be owned by the town itself (though operated by a private company on a contract basis).

The broadband infrastructure will cost $3 million, and resident voters on May 30 will say yay or nay to the plan to borrow that money. Like the St. George vote, the Islesboro proposal has economic consequences. It's a big-ticket expense, but it would help residents operate island-based and home-based businesses more effectively. And a big upside is that by virtue of the town ownership, fees can be held in check—no for-profit company hiking rates, simply because it can.

Town meetings are only the tip of the iceberg of town government. Most of the work gets done by citizens whose token remuneration equates to less than minimum wage.

In the very small towns, the clerks and selectmen are doing paperwork late into the evening at the dining room table, or taking phone calls first thing in the morning from the guy fixing the road and the builder who wants to start his new subdivision immediately.

On Isle au Haut, the island town off Stonington, the annual town meeting has been postponed; as of our publication deadline, a date certain has not been set. Islanders have said the tedious but critical work of managing the town's finances was not done over the last year or so, leaving the town meeting—which is, legally speaking, the municipality's legislative body—in limbo.

If no malfeasance is evident—and all hope that is the case—then we hope residents can be forgiving of those who dropped the ball. This, too, is a decision that lies with the locals, as well it should.

Contributed by