Posted July 18, 2017

Last modified July 18, 2017

This column first appeared in the 2017 Island Journal, which is now available for purchase at TheArchipelago.net.

Maine touts its allure for visitors and prospective transplants by asserting that we provide qualities summed up as “the way life should be.” The phrase suggests purity, simplicity, a pace more in tune with nature. Our island communities embody those qualities in concentrated form.

So it might seem odd to posit that without fast internet—something that seems antithetical to “the way life should be”—those island communities are facing stagnation, a declining labor force, an aging population, and evaporating economic opportunities.

The Island Institute’s analysis, as well as that by others working to improve life here, definitively reveals that the lack of broadband—a measure of internet speeds for uploads and downloads—is indeed a threat to island life.

To understand this threat, imagine being a 22-year-old college grad, considering beginning your new life on the coast of Maine, the place your parents have been visiting for much of your life. Or perhaps you were born and raised on a Maine island, and hope to make a life in the place your family has called home for generations.

But putting roots down in this special place is something like trying to farm on a rocky island—possible, but much harder than it should be.

Our young adults understand that access to consistent, reliable broadband internet is more than a luxury. It’s about more than Netflix and Amazon Prime. It’s as essential to community and economic vitality as deep, rich soil is to the would-be farmer.

Many think the role high-speed internet plays in our lives is akin to cable TV or a subway system; nice to have, but not necessary to make a living. A young man who lives on Chebeague Island with his wife and children telecommutes to his job with IBM. And a recent story in The Working Waterfront told the tale of a Chebeague fisherman who used the internet to purchase parts from across the globe to rebuild his boat’s engine.

Artists and architects need quality internet to show their work to clients. Restaurants and stores need it to manage credit card sales. Physicians and counselors use video conferencing over the web to consult with and diagnose patients. Young and older workers are able to live on the Maine coast and attend meetings via that same videoconferencing technology with co-workers across the country.

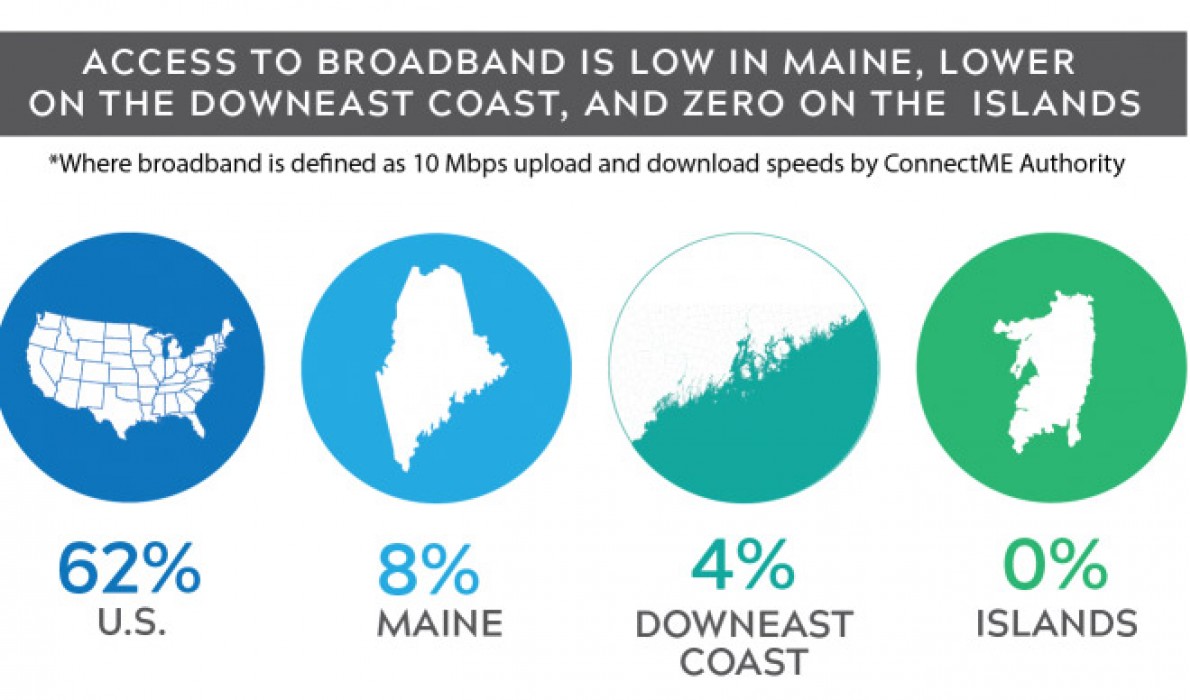

But the state of internet speed on the islands and Maine coast is poor. According to recent data presented in the Island Institute’s Waypoints: Community Indicators for Maine’s Island and Coast (see islandinstitute.org/waypoints), 8 percent of Maine residents are served by internet speed characterized as broadband, 4 percent of the Downeast coast is served at that speed, and none of Maine’s island communities now have broadband. Broadband is defined by the state as upload and download speeds of 10 megabits per second.

According to the Connect Maine Authority, the annual sales of Maine’s sole proprietorships and small businesses amount to about $21.7 billion a year. If these enterprises were served by broadband at the national average, the result would increase annual sales by nearly $50 million a year.

Large scale broadband providers have not invested in the infrastructure that could allow communities to access the average national speed, unable to make a business case because of the lack of potential customers in rural areas.

How, then, will the lack of broadband be resolved? To date, the state and federal governments have not made significant investments in solving the problem. Given these circumstances, the community ownership option might be the best solution.

Islesboro and the Cranberry Isles have decided to build their own broadband infrastructure and then lease it to a provider. Chebeague, Long, and Cliff islands recently published a joint request for information on how to improve their infrastructure. Maine has several small broadband utilities eager to compete for contracts to serve these communities, and larger service providers also have expressed interest in working with island communities.

As with many issues these days, the community scale is going to be the scale at which we meet our broadband needs.

To make it here in the coming years, community scale investments in broadband will be essential. We can look to the islands that have led first.

Rob Snyder is president of the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

Contributed by