Posted January 28, 2019

Last modified February 27, 2019

By Dana Wilde

Long ago, when I was a kid growing up in Southern Maine, we made road trips to Massachusetts to visit my father’s family. This was the late 1950s and early ’60s. Route 1 from about New Hampshire turned into a reeling commotion of cars and trucks, diesel smells, weird-looking roadside restaurants and liquor stores, and did I mention a rattling chaos of cars and trucks.

When we passed the Welcome to Maine sign on the way back, the cars and trucks thinned out. The scenery was made mainly of trees and brush, a bridge across a brook. A sense of openness and calm returned, a feeling of remoteness.

In the 1970s Massachusetts came rolling up the coast. But if you drive far enough Downeast, you can still feel that ancient, quiet Maine. Blueberry barrens and shuttered clam shacks. How far is that, exactly?

A poet with continent-spanning sensibilities can reveal it to you. Tom Sexton and his wife, Sharyn, drive from Alaska to Maine every other fall, spend the winter at their house in Eastport, then drive back to Alaska, where Tom worked more than 25 years as a poet and professor. One of the things he likes in both places is the solitude.

This year, he told me in a conversation in Eastport, the “drive south” took the Sextons through their native Massachusetts.

“We left Mass. on a Sunday morning,” he said, “and we were in almost bumper to bumper traffic from Salem to Ellsworth. Only at Ellsworth did it start to thin out.”

And on into Washington County, where remoter, quieter Maine still echoes.

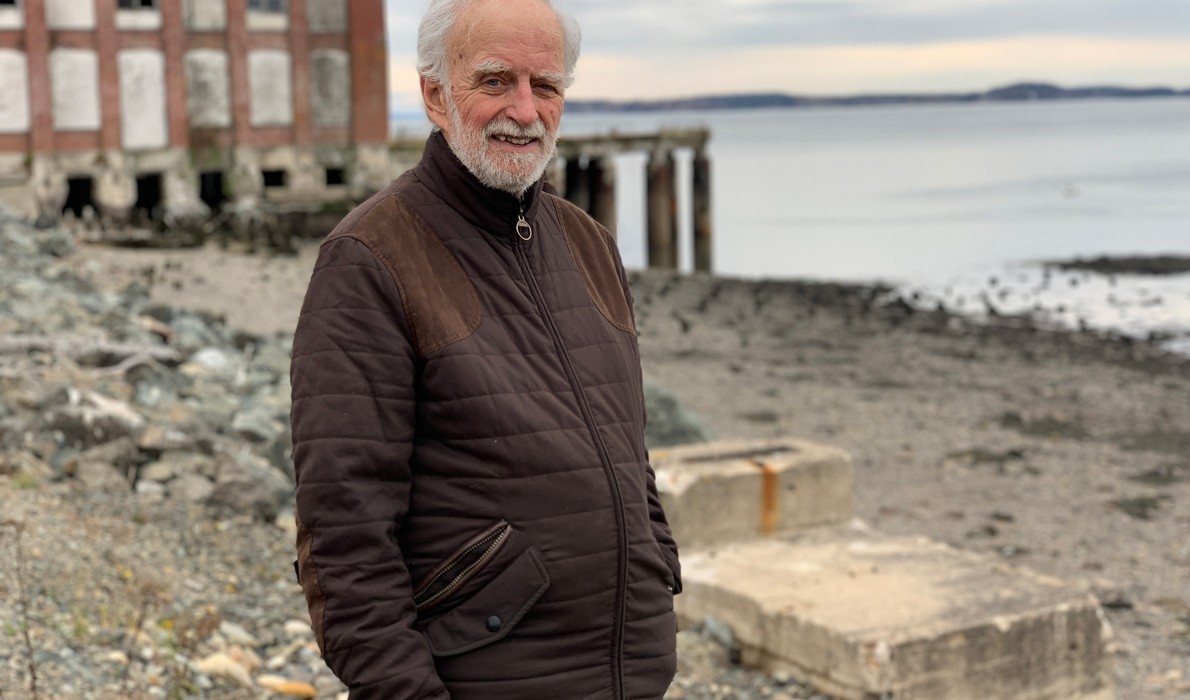

LURA JACKSON

Tom Sexton

“At the end of the world is where I’ve lived most of my life,” Sexton said. “And I enjoy that. On the edge.”

Sexton, now 78, served as Alaska’s poet laureate from 1995 to 2000, after retiring from teaching at the University of Alaska at Anchorage, where in 1970 he was one of the founding members of the new campus’s English department. He arrived there fresh from the MFA program in creative writing in Fairbanks, and before that grew up in the working class city of Lowell, Mass.

Along the way he was a founding editor of the Alaska Quarterly Reviewand has written 12 highly regarded collections of poetry, most of them assembled after his retirement in 1994. Around that time, as they took stock of their possibilities, Tom and Sharyn were invited to spend a winter on Islesboro. They liked it, and “kept driving” up the coast, where Maine’s still quieter shadows come into focus. In 2001, they found the house in Eastport, where they’ve spent every other winter since.

Mirroring his life in some ways, Sexton’s poetry gets its energy from the landscapes on both edges of the continent. His many lyrics on Denali, the Alaskan outback, and “driving north” contrast with the moods and scenes of Maine’s rocky fields, Passamaquoddy Bay, and coastal beauty. “Eastport, Maine,” from the 2015 collection “A Ladder of Cranes,” concludes:

A dragger, light on, heads for the breakwater.

Over Campobello Island, moon rising, scallop-white.

The unhurried profundity of the Downeast coast is captured by placing images side by side without comment, a style characteristic of ancient Chinese poetry which Sexton has read in translations and admired for years. His newly published book, Li Bai Rides a Celestial Dolphin Home,includes a series of short poems imagining the eighth-century poet Li Bai making his way home from a cabin in Denali National Park, where Sexton dwelt several years ago while serving as the park’s artist-in-residence.

“Li Bai” is heavier on Alaska than Maine, but his retrospective selection For the Sake of the Light(2009) contains many observations from eastern Maine, with titles like “Passamaquoddy Bay,” “In Waldo County, Maine,” and “Crossing the Blueberry Barrens.” In all these poems, you sense the poet holding still in the stillness, and appreciating the tremendous beauty that filters through quiet places when you listen.

Sexton calls Eastport a “triggering town” that is, for him, a launching point to “the bend toward the Atlantic … back into the past where my Irish ancestors came from,” he said.

“Who wouldn’t get an idea for a poem when you’re standing on Water Street and the wind’s blowing 50 miles an hour and piling up?”

When asked if there are differences between the poetic material found on the two edges of North America, he points without hesitation to different qualities of light. In Eastport, it’s “a soft light,” often wrapped in fog, rising over Campobello; in Alaska ,at “the bend toward Asia,” it’s “a hard light, intense and very clear … you can almost see through Denali.”

He says Eastport’s quietness is amenable to his own somewhat reclusive lifestyle, noting, though, that “there’s always something going on” in the island city. In the 17 years the Sextons have been alternating coasts, a vibrant arts culture has grown up, he points out, with new art galleries, bed and breakfasts, the Eastport Arts Center, and the Tides Institute, with competent support from the local Quoddy Tidesnewspaper. The creative economy, “whatever that means, has done wonders in the downtown,” he said. “Even in the middle of winter, someone’s putting on a show practically every weekend.”

A few years ago, he said, “I gave a very well-attended reading at the arts center. I think it drew as many or more people than it would in Anchorage.”

Sexton got to Alaska in the military in the late 1950s, returned to Massachusetts where he worked odd jobs, and then went to college on the G.I. Bill at Salem State University, where he and Sharyn met. He gravitated toward English classes and got interested in writing, which led to the MFA program back in Fairbanks. When the new campus in Anchorage opened, the administrators called him in and offered him a job.

“I was extremely lucky,” he said.

His Massachusetts roots appreciatively colored his entire teaching career, culminating in A Clock with No Hands(2007), a verse reflection on his childhood.

In some ways, Eastport seems as natural to him as his other homes.

“I like the idea that there’s still a working class here,” he said as we admired the boats tied up on the Eastport waterfront. And he pointed out, wryly, that the nearby statue of the fisherman holding a fish is a nice gesture in the direction of the local working people, even though it’s dedicated to a reality show actor and 9/11 victim, and no fish like that has ever been caught in Passamaquoddy Bay.

But it’s the quiet he cherishes, the sense of remoteness yet proximity to civilization, what Thoreau, one of his anchoring writers, called the middle distance.

“I’m quite happy in my shell,” he said. “[Eastport] is a good place to live, if you can manage a little solitude.”

That is, in a word, the mark of my Maine too.

Tom Sexton’s recent books are available from University of Alaska Press.

Sea Street

Eastport, Maine

By Tom Sexton

The first harbor seal I’ve seen since

my return to Eastport takes my measure

then slips beneath the placid water.

It’s the golden hour suffused with light.

I watch an urchin dragger move away.

Picturesque, but its days grow longer.

Its iron maiden drag holding only air.

When the moon’s full, the tide high

I hear Arnold’s eternal note of sadness

in the waves. Yesterday, a friend asked,

“Why do we read poetry at all today?”

I had no answer, I have no answer now.

St. Brendan thought the Right Whale’s

song, soft as a harp through mist, a hymn.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy and writes the Off Radar column for the centralmaine.com newspapers; his recent book is Summer to Fall: Notes and Numina from the Maine Woods.

Contributed by