Posted January 21, 2020

Last modified February 25, 2020

By Tom Groening

Jeremiah Hacker is not more than a footnote in Portland’s history, let alone Maine’s history. But examining his work as a crusading journalist through the middle of the 19th century opens a window on a world wrestling with slavery, brutal prisons, poverty without social safety nets, a rising but ruthless industrial economy, and the decline of the family farm and the moral and social values embedded in that change.

What began as Rebecca Pritchard’s master’s thesis at the University of Southern Maine became Jeremiah Hacker: Journalist, Anarchist, Abolitionist, published in 2019 by Frayed Edge Press, an engaging and colorful read, much like its subject.

Though Hacker may accurately be described as a crusading journalist, he was no precursor to Bob Woodward or Carl Bernstein. He never would have been described as fair and balanced. In fact, he used his newspaper like a protestor’s placard. Or maybe like a club.

Still, an endearing eccentricity and admirable passionate righteousness emerge in reading about Hacker and the battles he fought with his self-published newspaper, The Pleasure Boat.

“He was just so out there,” Pritchard said in a recent interview, and she confesses to having developed a fondness for her subject.

“I like him very much. I find him kind of odd, as I’m sure people did at the time. People probably rolled their eyes a lot,” she added with a laugh.

In the opening pages, we learn that Hacker was a tall man who walked the same route through Portland each week, perhaps beginning at the printer’s shop on Exchange Street, carrying under his arm copies of his newspaper and a hearing trumpet, helping to compensate for his near deafness. Pritchard compares him to his namesake Old Testament prophet, striding through a world he saw as decadent and full of those ready to prey on the gullible.

Hacker embraced the unadorned Christianity of Quakerism, and in fact railed against those who were employed in the institutions of organized religion. Yet later, after years of attacking what he saw as the charlatans who purveyed contact with the dead for the grief-stricken, he began accepting spiritualism as a legitimate.

Pritchard describes him selling The Pleasure Boat to those he encountered on his walk, though “He did not always meet with success, but neither did he give up easily.” In one encounter in which a man refused the sales pitch because he claimed the newspaper was “full of lies,” Hacker insisted he have a copy anyway. “He asked the man to ‘read it and mark all the falsehoods with a pen, and return to me, so that I may be sensible of my errors.’”

Much of what emerges in Pritchard’s study of Hacker comes from his newspaper’s pages, but she quotes an account of the man by a fellow journalist: “a good man, possessing great benevolence … working hard among the poor and despised.”

NEW ENGLAND REFORMER

Hacker’s views were consistent with other New England reformers of the day, but as Pritchard notes, we see the issues through Portland’s history, where the newspaper circulated from 1845 to 1862.

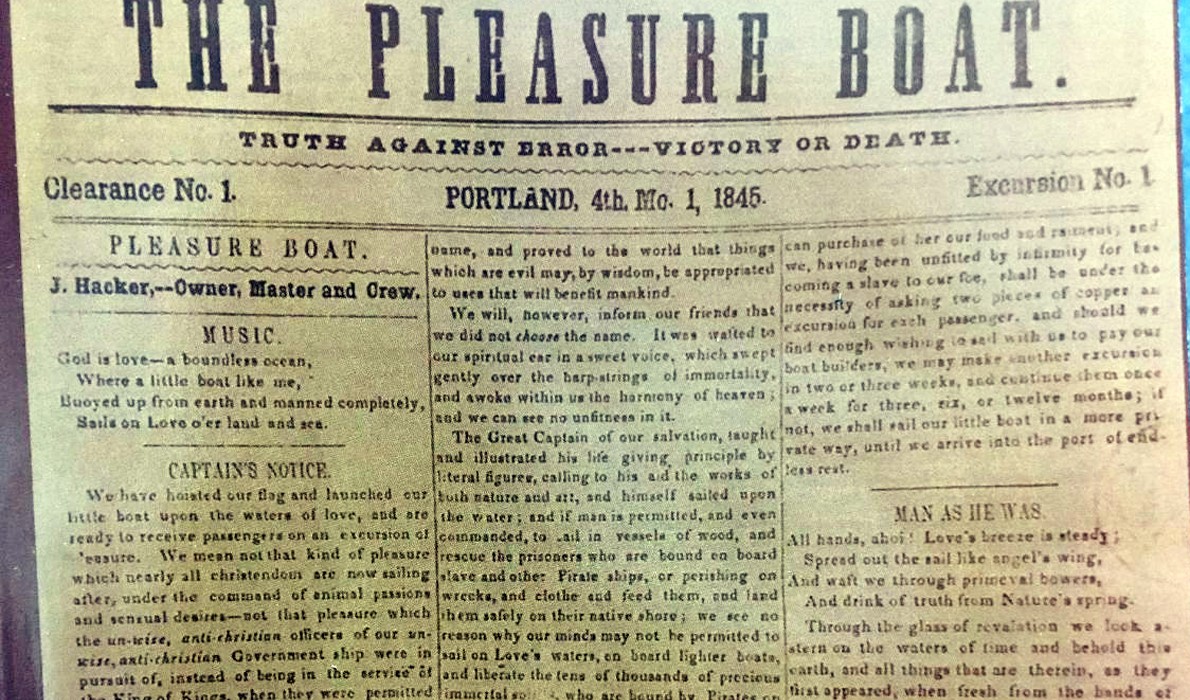

The first issue of The Pleasure Boat declared its intent: “We have hoisted our flag and launched our little boat upon the waters of love, and we are ready to receive passengers on an excursion of pleasure … that pure, present, and eternal pleasure in which the immortal spirit of man lives and breathes.”

Pritchard writes that Hacker “emerged as a genuine homegrown radical whose newspaper gave voice to many of the more revolutionary ideas that were floating around at the time.”

And those ideas, she writes, were born of the era’s “fever of reform.”

A central idea driving Hacker’s efforts was his radical belief that everyone should be able to access land on which to farm without having to pay for it. The “free land” movement was couched, in part, in a disdain for the horrors of early industrial urban life. “In cities the air is impure, water is impure, much of the food is impure, many of the customs and habits of city life are impure,” Hacker wrote.

But the main thrust of Hacker’s free-land ideas was economic. He argued the Irish potato famine was the result of “land robbery,” and that America was headed for similar disasters. The solution, Hacker argued, was “to give every man, without money or price, as much land as he will cultivate with his own labor,” and “allow no man to speculate in land.”

The reforms he touted also included his view that people should not need the strictures of organized religion to embody Christian values. He often savagely condemned those who accepted money for elaborate church buildings and salaries to minister to their congregation.

Hacker, Pritchard informs us, “wrote of destitute elderly couples with health problems who still had to work for meager pay and chop their own firewood. He wrote of widows with no money, food, or firewood. He described the children of these widows … lugging pails of swill home to feed their mother’s pig…”

He named some of the desperate families he encountered in his travels in his newspaper, and chided readers to help them.

His reform ideas were nuanced, though. He agreed alcohol took a toll on society, but instead of jumping on the temperance bandwagon, Hacker argued that movement was too rigid and uncompromising. He dismissed Portland’s famed temperance leader Neal Dow as “a mad dog with a firebrand to his tail.”

Hacker supported abolishing slavery, but again, was an outlier within the movement, arguing, Pritchard writes, “that slavery was everywhere,” including in factories and on ships, and that “well-to-do abolitionists” who owned large tracts of land ought to end “slavery” in the North.

Pritchard argues that Hacker is worthy of academic inquiry for his first-hand account of Maine 19th century history, including the anarchist and reform impulses that played out here.

“He was an articulate witness to his times,” Pritchard eloquently writes, “even while making clear that he wished his times were different.”

Pritchard, who is the daughter of famed Maine storyteller and humorist John McDonald, credits librarian William David Barry for introducing her to Hacker. Her master’s thesis was guided by Ardis Cameron and Joseph Conforti.

To purchase the book, see: https://www.frayededgepress.com/jeremiah-hacker.htm

Contributed by