Posted April 18, 2019

Last modified April 25, 2019

By Jack Sullivan

The threat of Lyme disease presents complications that leave many of us flummoxed, but thankfully, Mainers—especially islanders—are problem solvers by necessity.

Many of the challenges mainland communities face are exacerbated when faced by an island. Some of this is obvious. Of course it’s harder to get a high-speed internet connection when there’s a body of water between you and a provider.

But why is someone twice as likely to contract Lyme disease on certain Maine islands as they are on the coastal mainland?

I sought the answer to that question, and what community leaders are doing to address this serious health threat. The inquiry first took me to Cape Elizabeth, where I met Dr. Peter Rand and Chuck Lubelczyk of the Lyme & Vector-borne Disease Laboratory at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute. Both are experts in the field of tick-borne disease management.

It was here that I learned the history of Lyme disease, the ecology of the dreaded deer tick, and the fascinating story of how Rand, Lubelczyk, and their colleagues worked alongside the residents of Monhegan Island in the 1990s to execute an effective (albeit controversial) program to eradicate Lyme disease from the island.

Monhegan’s Lyme disease saga begins with the introduction of two species to the island. One, the Norway rat, likely was established on the island hundreds of years ago, stowed away on the ships that bought the island’s early settlers. The other was brought to the beautiful island in the 1950s in an effort to make it even more beautiful—the common white-tailed deer.

Having deer and rats to feed on, and a warming climate and supportive vegetation, created a conducive habitat for a third, more insidious species: Ixodes scapularis, the deer tick.

After several efforts to eliminate Lyme disease from Monhegan failed, a last-resort plan was put into action: every single deer on the island was dispatched by a sharp shooter. Within a few years, the cases of Lyme disease on the island dropped to almost zero. This method is still the only means of eradicating Lyme disease that has proven effective, and no community has done it since.

Such a strategy wouldn’t work on many islands, given their larger size (for example, Monhegan has 4.5 square miles of land compared to Vinalhaven’s 169 square miles). Other islands are so close to the coast that deer can swim there, so if the population were wiped out, a new population would likely reestablish itself eventually.

Islands like Islesboro have annual hunts—and even special hunts outside the normal hunting season—to help control the island’s deer herd, but many of the residents are opposed to eliminating the entire deer population because the annual hunt is so ingrained in island culture and tradition.

“It’s not a broad-brush approach,” Lubelczyk said of his work on islands. “You have got to treat each island almost individually. And you have to craft a tick program or a tick management program to each island’s needs.”

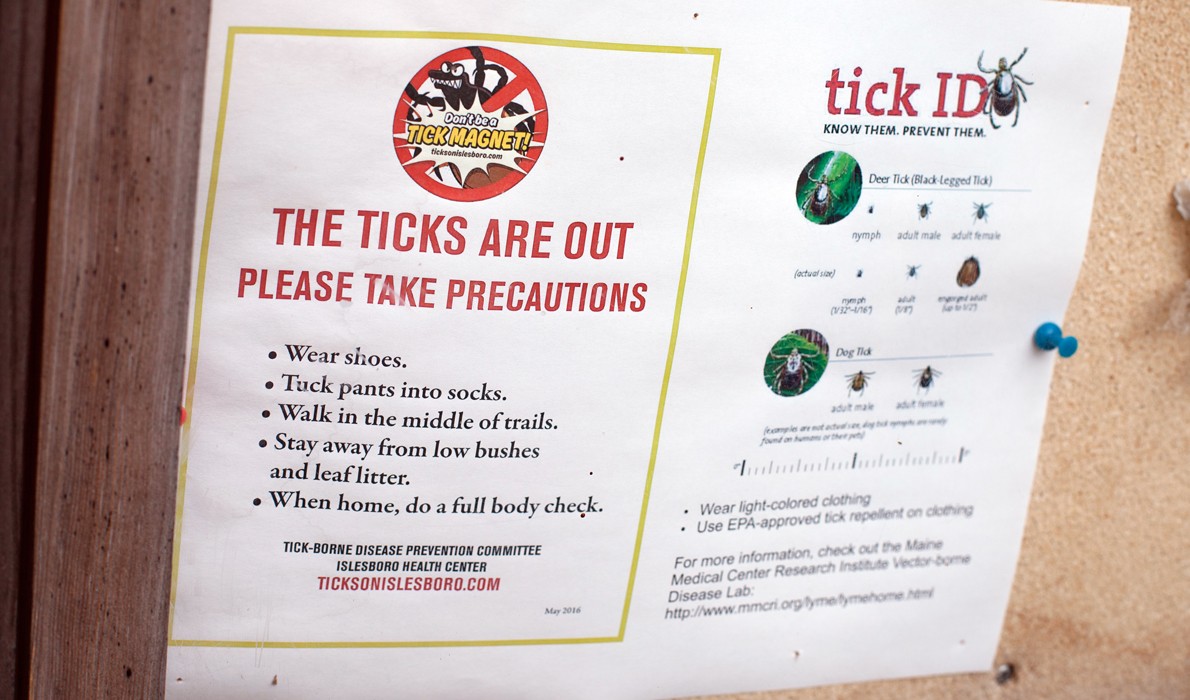

Even though islands may experience the same problem, that doesn’t mean they’re going to use the same problem-solving methods. That’s where island leaders like Linda Gillies and Derreth Roberts of Islesboro, and Donna Wiegle of Swan’s Island come into the scene. Gillies and Roberts serve on Islesboro’s Tick-borne Disease Prevention Committee, which primarily aims to educate residents and visitors about how to protect themselves and what to do in the event of a tick bite. The committee has printed and distributed pamphlets and posters around the island and it has information disseminated digitally.

Wiegle, director of the Swan’s Island Health Center, helps patients who come in with tick bites, hosts informational programs for the public, and works in other capacities to fight tick-borne diseases on her island.

To read comprehensive interviews with these individuals and to learn more about Maine’s island tick problem, the community leaders on the front lines, and their methods to thwart Ixodes scapularis visit: www.islandinstitute.org/lyme.

Jack Sullivan is a multimedia storyteller at the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

Contributed by