Posted September 4, 2018

Last modified September 4, 2018

By Abby Barrows

Plastic—we all touch, use, and throw it out every day. It is an amazing, lightweight, and durable material. That quality of durability, however, has made plastic into a worldwide pollution problem. We use items designed to last a few minutes, made from a material that lasts thousands of years. Each year over 350 million tons of plastic gets manufactured, and only about 5 percent of that gets recycled. So yes, it is starting to pile up.

An estimated 8-10 million tons of plastic make their way into the oceans each year. To try to visualize that, think of five grocery bags of trash for every foot of coastline in the world. If we continue our current trend, those five bags will be ten by 2025. There are already an estimated 250 tons of plastic afloat in our oceans, the majority classified as microplastics.

Microplastic pollution is considered an emerging issue of international concern. Microplastics are pieces of plastic less than 5 milimeters in size. They have been found in all the world’s oceans, from the surface to deep water trenches, in freshwater environments, tap water, bottled water, beer, honey, salt, and even in our air.

Since the study of microplastics is still a relatively new field of science, the more places researchers look, the more places we find them. So why should we care about these ubiquitous little plastics? There are a number of reasons to be concerned.

First, the aquatic environment contains many ambient toxicants; most of these are known as persistent organic pollutants, or POPs—compounds that are resistant to environmental degradation (such as DDT or PCBs). The physical and chemical properties of plastic attract and concentrate these chemicals, sometimes up to a million magnitudes higher than surrounding seawater.

Plastics also releases the hazardous additives that they are made with into the environment. The majority of the chemicals have known negative human and environmental health effects. So a tiny, seemingly insignificant piece of plastic can become a toxic sponge, transporting POPs and their associated additives around the world and into different habitats and animals.

Unfortunately, when plastic is consumed by animals either directly or indirectly through consuming prey that contains plastic, the toxins from and on plastic can leach into an animal, finding a permanent place in the food web.

We still don’t understand what amount of plastic interaction will have long-term health effects on the population or community level, but we do know that laboratory studies have shown associated behavior changes, reduced reproduction and energy uptake, and diminished offspring performance in animals that have ingested microplastic.

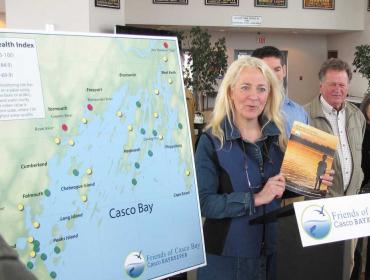

My five years of research on microplastic contamination in global surface waters show there are no places on the planet not affected by plastic pollution.Working with the non-profit Adventure Scientists, and College of the Atlantic, we found an average of 12 microplastics per liter of water, with higher concentrations in the open ocean than coastal sites. The Gulf of Maine is quite contaminated, with coastal samples containing the second highest average (8 pieces per liter) of any region within the Atlantic Ocean.

What do we do with this knowledge?Plastic pollution is a complex problem which needs some complex solutions. It is clear that we need to rethink how we use single-use plastic in our daily lives—we can no longer just throw it away, as there is no “away”on this planet. We need to use data and legislative tools to put our awareness into real and effective change.

Abby Barrows grew up in Stonington and received her B.S from the University of Tasmania and her M. Phil from College of the Atlantic. She has directed global microplastic research since 2012 and initiated the first baseline data map of microplastic pollution distribution in coastal Maine.