Posted April 26, 2017

Last modified April 26, 2017

By Phil Showell

It was one of those crazy thoughts people get in the dead of winter. It’s January of 1608. You’re a Popham colonist, teeth chattering, huddled against the cold in a half-built Fort St. George. Up drives a snow-splattered Jeep Cherokee with a license plate proclaiming “Maine–Vacationland.”

Well, without a forward-looking time machine, the irony or even humor of “Vacationland” would surely have escaped the colonists. Recognizing only daily hardship, they had come to exploit the riches of The New World. But soon they would return to England as survivors of a failed gamble whose details were probably only mumbled in pubs.

However little recorded—in rumors and scraps of memoirs—the venture was nonetheless a remarkable, fascinating piece of the history of Maine, of the nation and of ship-building in America.

Fortunately, hundreds of volunteers have spent thousands of hours at either a 25-year archeological “dig” to confirm the site of the brief settlement or in the current reconstruction of Virginia, the pinnace built there at the mouth of the Kennebec River. It was the first ship built by British colonists in America, and also the first of more than 1,400 ships built since along the banks of the Kennebec River, a volume of shipbuilding unequaled anywhere in the nation.

WHERE WE’VE BEEN

In our out-of-breath, digitized society, “history” is more often denigrated than revered; it’s too often considered what’s “done with” and unworthy of attention. Still, to know where we should be going, we’ll always need first to know where we’ve been. So, it’s time to salute all those full- and part-time Mainers who undid the shrouds of time wrapped round the Popham Colony of 1607-08.

Last fall saw two milestones in documenting the colony’s brief existence. The first was publication of Fort George II, the concluding volume of Archeologist Jeffrey P. Brain’s intriguing report of the excavations he led from1994 to 2013. The “digs” proved the fort’s long-rumored existence at the mouth of the Kennebec beyond doubt.

This is far more than a catalog of the artifacts exhumed and analyzed. Brain gives the political, economic, and social context in which this bold adventure was planned and carried out. It is a model of thorough, illuminating documentation, which raises some provocative questions:

- Why was such a well-planned and equipped venture abandoned after only nine-months? (Brain suggest it was for want of money and strong leadership.)

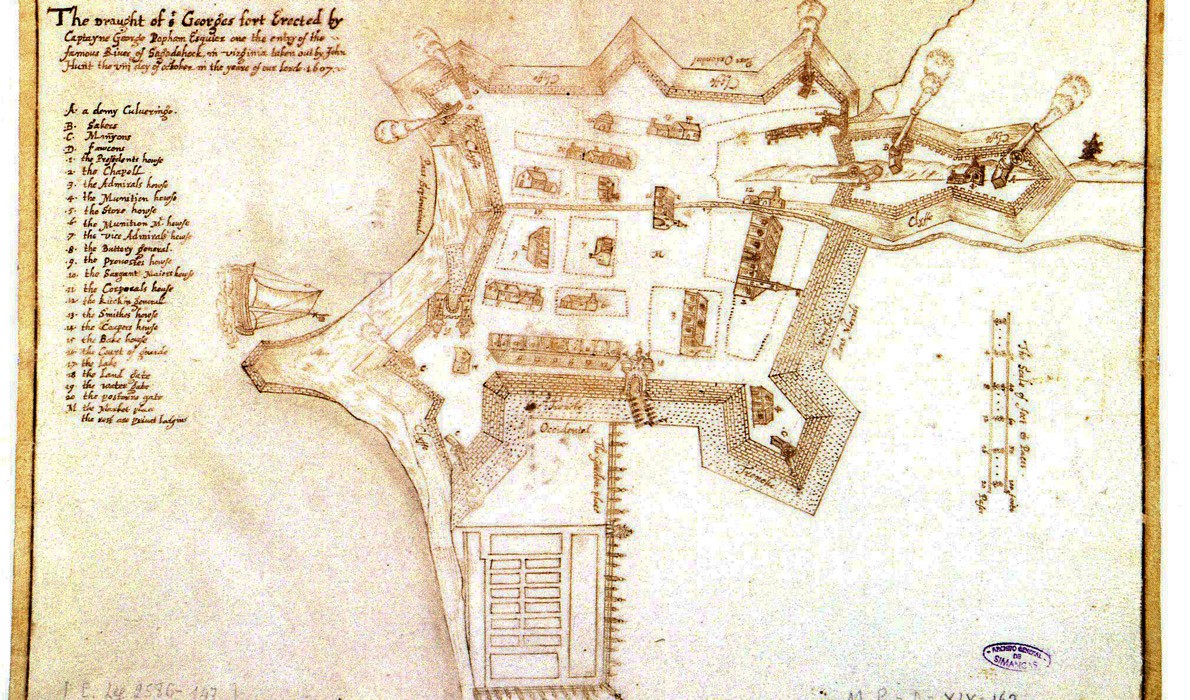

- How did John Hunt’s amazingly accurate 1607 map and plan of Fort St. George wind up in the archives of the Spanish government?

Born of the ongoing war between England and Spain, a persistent yarn was that the map was stolen by a Spanish spy. But copies remained in London and were used hundreds of years later to pin-point targets for excavation. The most plausible theory now seems to be that the map of the fort was propaganda, sent to Spain to discourage any thoughts of settling the Maine coast.

COURTESY PAUL CUNNINGHAM

A marker denotes the location of the Popham colony.

The second milestone was put in place last fall by Rob Stevens, master shipwright with the nonprofit Maine’s First Ship, the project now pursuing a thoroughly researched reconstruction of the first Virginia. The original seaworthy ship, built in six months, ultimately made at least two Atlantic crossings. Stevens estimates the Virginia replica is “half done.” His encyclopedic knowledge and experience with ages-old tools and techniques is at work supervising a crew of volunteer ship-builders.

Orman Hines, president of Maine’s First Ship, looks ahead to the day when sailing aboard the completed Virginia will enable “schools and the public to experience the early history of Maine and its remarkable shipbuilding industry.”

COMMERCIAL GAMBLE

The Popham settlement was not prompted, as later efforts were, by religious or political persecution. It was a purely commercial gamble backed by interrelated families from around the English port of Bristol. They included Sir John Popham, Lord Chief Justice of England and reputably its wealthiest citizen. George Popham, an elderly relative, was named president (leader) of the expedition with 25-year-old Raleigh Gilbert as admiral (second in command).

They led the northern half of a two-pronged effort to settle and exploit the Atlantic coast of Virginia, as America was then known. Under a charter from King James I, the more fortunate, southern-bound group landed at what became the permanent settlement of Jamestown two months before its twin company landed at the southern tip of the Phippsburg peninsula.

Carpenters, shipwrights, and workmen of all necessary disciplines were among the 100-plus colonists who set sail from Plymouth on May 31, 1607. Eleven months later they would learn that their foremost backer, Sir John Popham, had died before they even reached the Azores. Unaware, the colonists worked doggedly even as native Abenakis threatened and a fierce winter set in.

They built a warehouse, moved all the supplies remaining in one of the ships that had brought them into it, and then more than half the colonists boarded the now-emptied ship for the trip home. That, of course, improved chances of survival for the 45 who remained. It may well have done so. But on Feb. 5, George Popham, who some had considered too infirm to make the trip, died. And the dying continued.

A supply ship, arriving in the spring, reported things were going swimmingly; the fort was “well advanced” and Virginia had been completed and launched. But it also brought word that Sir John Gilbert also had died. That prompted Raleigh Gilbert, now the Popham Colony’s flashy 25-year-old leader, to hop aboard to get back to England to claim his inheritance.

Suddenly, what appeared about to become a successful settlement was leaderless. The Popham Colony was abandoned. Instead of plying coastal waters for trade, Virginia was used to take the remaining colonists home.

That succession prompted archeologist Brain’s strong belief that the colony’s failure had more to do with lack of financial support and poor leadership than with any short-comings of their amazingly industrious followers. The habit of putting landed gentry in the top jobs, he notes, was a dicey hang-over from feudal times.

CREDIT DUE

Brain’s contribution to what is now the established history of the Popham Colony can’t be over-estimated. Recruiting professionals, raising funds, negotiating state and local permissions, educating volunteers, researching the context, his work was indispensable to a complex, 20-year exploration.

Brain focused on the Phippsburg site after a quarter-century of dispute about the location of Fort St. George. The necessary and ongoing encouragement for both the “dig” and a reconstruction of Virginia was provided by Jane Stevens, a retired school teacher who suspected, correctly as it turned out, that she was living on the site of the fort. The idea for building a new Virginia was hatched at her kitchen table.

History is dynamic but inaccessible until people sit down and write. So we are thankful for Brain’s Fort St. George and Fort St. George II and for the equally thorough Virginia by John W. Bradford, an account of the extensive research that produced designs for the reconstruction now underway. It can be ordered from Maine’s First Ship’s website, ship.org.

Questions remain. Why has the legislature not designated Fort St. George a state historic site?

The Virginia was used to supply Jamestown after the Popham Colony disbanded. Did it carry the replacement leader who had to turn back colonists heading downriver to abandon Jamestown? Just a rumor, not yet history. But it’s “what ifs” and such multiple ironies that help keep history alive.

A final thought: Brain tells us that one of the “most haunting finds from all of the excavations was the case bottle that had been smashed against (a hearth) in the smithy… Whether it represents a final toast before the colonists boarded the ships homeward bound, or something more mundane, it is emblematic of the shattered hopes of a failed venture.”

Just imagine it.

Phil Showell is a summer resident of Phippsburg.