Posted September 17, 2020

Last modified September 17, 2020

By Laurie Schreiber

Acoustic buoy releases and tracking software: These are high-tech options under consideration as ways to eliminate the potential for interaction between the lobster fishery and the endangered North Atlantic right whale.

Ideas include raising traps from the sea floor by means of acoustically signaled lifting mechanisms, rather than hauling by vertical ropes that stretch from the floor to surface buoys.

Fishermen aren’t enthusiastic. In one survey, they cited the cost of converting to ropeless fishing—as much as $350,000 per boat—and the challenges of operating digital devices needed to work the acoustic system while they’re suited up in challenging sea conditions and winter weather.

“How can I deal with these devices with these gloves on?” one respondent told Libby Jewett, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Acidification Program and a board member with Stonington’s Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries.

Jewett conducted the survey last December and presented her findings during the MCCF’s Lunch & Learn Series in July.

She interviewed 14 lobstermen, along with fishery scientists and others, to get ideas on how to reduce the potential for interactions.

In July, the Switzerland-based International Union for Conservation of Nature changed its listing of the whale from endangered to critically endangered. It’s already in the Marine Mammal Protection Act and Endangered Species Act’s highest risk categories. About 400 individuals remain, and likely fewer than 100 breeding females. A high number of deaths in recent years was caused by vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglements, according to a NOAA investigation.

Climate change is exacerbating the intersection between right whales and the fishery, said Jewett. The Gulf of Maine is warming more quickly than most of the world’s oceans, she noted.

“This is causing all sorts of changes in this region,” including shifting distribution of Calanus finmarchicus, a plankton species that’s a favored right whale prey. Once abundant in the Bay of Fundy, Calanus is now seen more in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, likely due to changing water temperatures.

“Now whales are being found in great abundance in the Gulf of St. Lawrence” resulting in new interactions with fishing gear, Jewett said.

The lobster industry is also changing, she said. Fishermen traditionally fished in inshore areas. Now, more are setting traps farther offshore.

Changing whale migrations, along with a greater incidence of offshore fishing, could increase the risk of entanglement, she said.

The fishery’s major issue, she said, are those vertical ropes.

Options for reducing risk, she noted, include use of fewer lines or traps; lines that whales can easily break out of; and knowing whale whereabouts in order to mitigate risk of interaction.

As to ropeless fishing, options proposed include using a compressed air/bag lift mechanism that’s attached to the trap; an acoustic signal would inflate the bag and float the trap to the surface.

Along with responses that the idea would be too expensive and too difficult to manage, fishermen said it would result in a mess of trawls being set over each other because they won’t know where other trawls have been set. And they said it would take too long for traps to float to the surface.

Jewett said the answer could be additional technology—software that allows fishermen to detect each others’ trawls. Government subsidies could help bring down costs, she said.

Jewett also asked fishermen about the idea of adding more traps to a trawl, in order to reduce end line numbers. That resulted in concerns around safety; the need for bigger anchors in order to keep larger trawls in place, which could result in more gear on an entangled whale; and the higher likelihood that lobstermen will set atop each other.

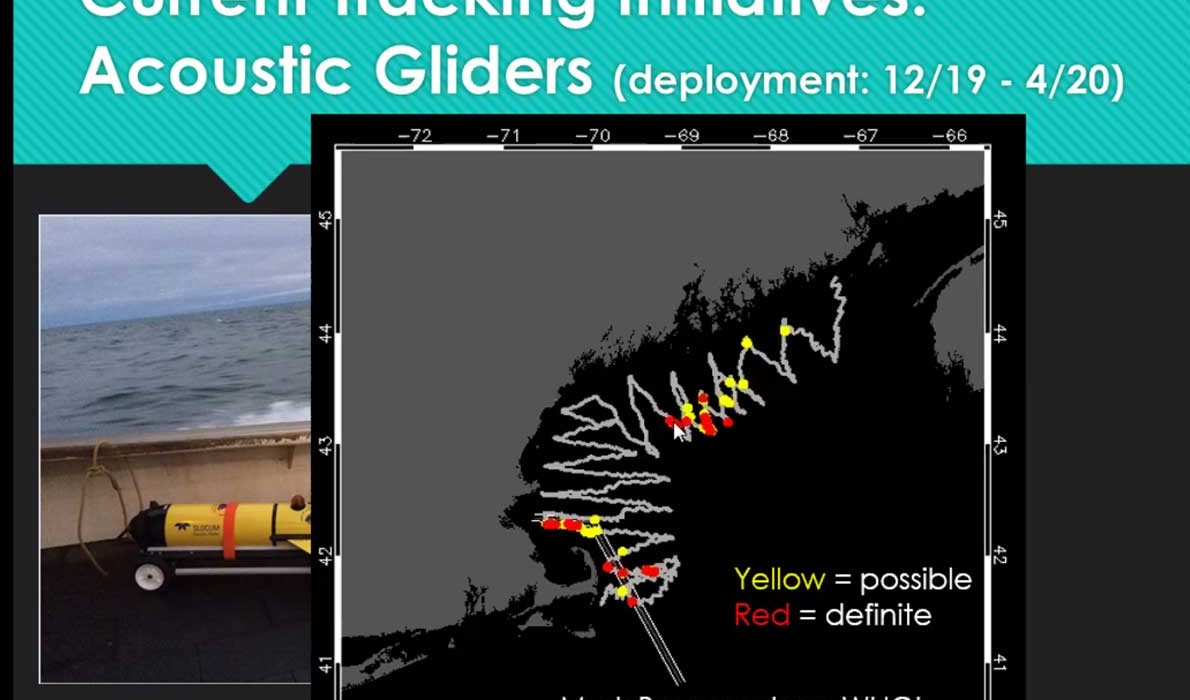

With only 400 whales, some fishermen suggested instituting a tracking system that would tell them when whales are present so they can remove traps. But, said Jewett, tracker tags can’t be inserted into North Atlantic right whales because of the risk of causing additional harm. However, she added, trial initiatives in recent months include Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s use of acoustic gliders, and deployment of acoustic monitoring buoys along the Maine coast in nearshore waters.

Another idea?

“Some fishermen said they would be willing to fish fewer traps, but only if mandated to do so,” Jewett said.

Lobster fishery’s sustainability certificate suspended

The Marine Stewardship Council suspended a sustainability certification for the Gulf of Maine lobster fishery as a result of a federal court case that raises questions about the impact of the fishery on the endangered North Atlantic right whale.

The council, headquartered in London, England, is an international nonprofit that uses its “ecolabel” and “fishery certification” programs to recognize sustainable fishing practices. According to its website, advantages of certification include enhanced reputation and promotional opportunities.

The suspension is effective Aug. 30. It came in response to a U.S. District Court ruling in April that found the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

violated the Endangered Species Act when it authorized the lobster fishery without appropriately analyzing its impact on the endangered whale. The decision was made in a lawsuit brought by a group of environmental organizations. The ruling triggered an expedited audit of the fishery. The audit found the fishery no longer met principles established by the council that are related to endangered, threatened, and protected species.

The certification is held by the Maine Certified Sustainable Lobster Association—a group of New England lobster wharf operators, processors, dealers and wholesalers. In a separate release, the association said it would work to regain the fishery’s certification after the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issues a new analysis regarding impacts to right whales.

Contributed by