Posted July 18, 2017

Last modified July 18, 2017

In August 1857, Penobscot Indian Joseph Polis paddled down the Penobscot River with Henry David Thoreau.

Polis had been helping Thoreau visit the Maine woods during the previous two weeks. Now coming into sight of Old Town Island, or present-day Indian Island, the seat of the Penobscot tribal government, Thoreau asked Polis if he was glad to be home.

“It makes no difference to me where I am,” Polis replied.

Polis’s answer offers valuable insight into the concept of “home” among the Penobscots and other Wabanaki tribes of Maine, says ethnohistorian, author, and University of Maine assistant professor Micah Pawling, who specializes in Wabanaki history in the 19th century.

“Home was not confined to a single place or bounded by walls or lines on a map, but was a feeling of contentment and belonging to a human network united across ancestral territory,” Pawling writes in his case study, “Wabanaki Homeland and Mobility: Concepts of Home in Nineteenth-Century Maine,” published in Ethnohistory, a journal published by Duke University Press, in October 2016. “Their movements contrasted with the European concept of a sedentary home limited by specific parameters.”

Pawling explains he’s interested in the 19th century history of the Wabanaki because it was a remarkable time for both change and continuity.

“A lot of Wabanaki history explores Native experiences in the Colonial period,” he says. “Then there’s a void, and somehow we jump to modern times. It seems to me there is a lot of work to be done in between.”

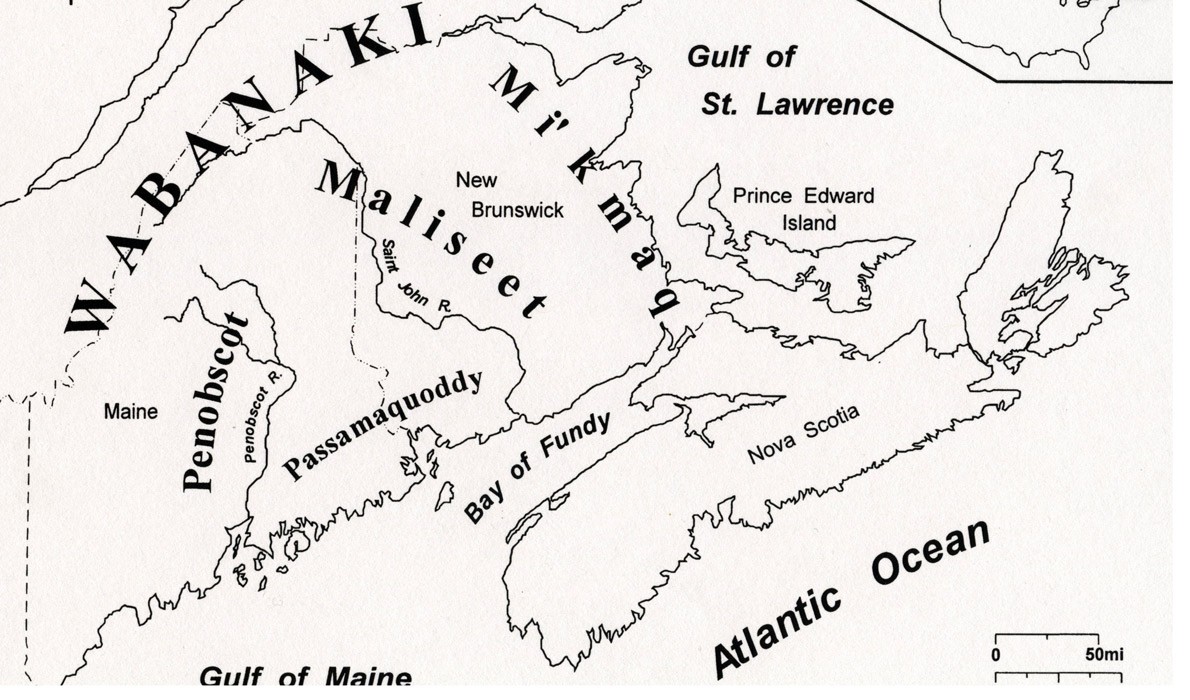

“Wabanaki,” roughly meaning “People of the Dawn,” refers to the Penobscot, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Mi'kmaq, and Abenaki tribes in northern New England, the Maritime provinces, and the southern shore of Quebec.

The 19th century, Pawling says, was difficult for the Wabanaki. Accustomed to moving at will between land and water to hunt, fish, and gather, they were increasingly dispossessed by Euro-American treaties and deeds.

Still, he says, the Wabanaki retained many cultural practices. For example, in addition to living on reservation islands and camping in the interior, the Penobscot remained active along the lower Penobscot River and its large bay with its rich marine resources. The Wabanaki reoccupied the Kennebec River Valley in small enclaves, harvesting natural resources, long after being dispossessed.

“In the 19th century, Wabanaki peoples refused to be confined to their reservations and acted with a significant degree of mobility across their traditional homeland,” Pawling writes. “Rather than adhere to the rigid settlement expectations prescribed by the Maine government, Wabanaki peoples clung to their mobility as key expression of their collective identity and their sense of homeland…”

WATER DEPENDENT

In the rivers and lakes, they fished for salmon, shad, and eels. In the ocean, they hunted seals and harbor porpoises. They gathered birchbark to make canoes, a primary mode of transportation along Maine’s extensive waterways, and excellent both for portaging and for its buoyancy in rough conditions.

But Wabanaki people sometimes collided with private property laws, increasingly had to navigate around the growing density of European settlement, and suffered from European depredation of the natural environment. For example, at the Passamaquoddy reservation of Pleasant Point (Sipayik) on Passamaquoddy Bay, this summer camping ground was rich with marine resources and was a favorite place for hunting harbor porpoises. By the 19th century, however, much of the bay’s western coastline had been cleared of trees, leaving the tribe without firewood for heat and food preparation. Similar depredation occurred on the Saint Croix River, a prime salmon fishing spot until the installation of dams prevented salmon and other anadromous fish from ascending the river to spawn.

Movements varied by season, as the Wabanaki followed the resources. They also varied by demographics. There’s some evidence, for example, that women, children, and the elderly camped in Brewer while the men hunted around Moosehead Lake. Reviewing historical documents, says Pawling, “I get the sense that it was more dynamic than we might have once thought.”

Wabanaki people primarily traveled by birchbark canoe.

“They still relied on their indigenous technology, the birchbark canoe, even in the late 19th century, when it became more difficult to harvest large white birch trees,” says Pawling.

This relationship with the water went beyond travel.

“It’s that knowledge about the tide and the weather, when to go and when not to go,” he says. “For example, there was a Passamaquoddy camp at Gooseberry Point on Campobello Island. It was known as the place where the people would wait for the tide to turn before canoeing out to Grand Manan Island. While many of us today might check a tide chart, the Passamaquoddy had the expertise on the water, knowing when the tide was ebbing or flowing and selecting a particular route to traverse and how it was going to change from hour to hour or from season to season.”

In documenting Wabanaki movements in the 19th century, Pawling says he hopes readers will gain an appreciation of the long-time connections that Native people have with the natural environment in their homeland.

“It’s just a snapshot in time. But, in reality, their ancestors have been doing this for a very long time,” he says. “To have some awareness of these cultural connections to their traditional homeland is still very important. It’s not just an activity or an economic opportunity. Time and time again, people say, ‘This is not just what we do. It’s who we are as a people.’”

Contributed by