Posted August 25, 2016

Last modified August 25, 2016

By Douglas Rooks

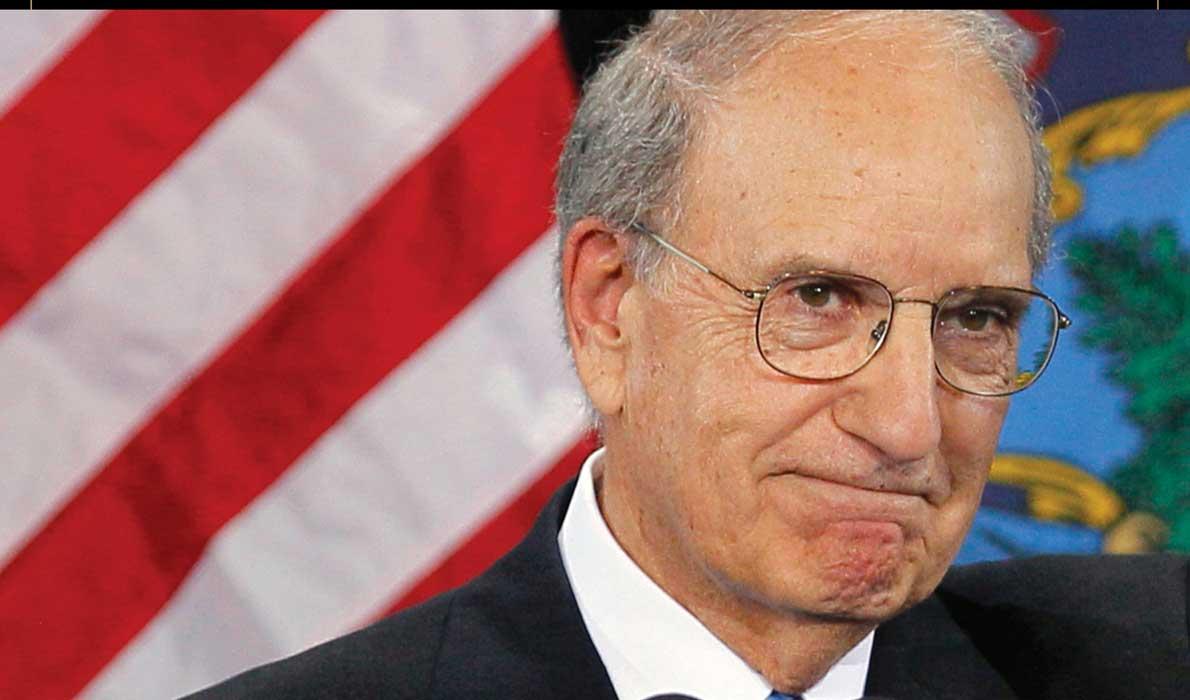

When I began researching Statesman, my biography of Sen. George Mitchell, I thought I knew the man, at least in his public life. After all, we first met in the Kennebec Journal newsroom in Augusta some 30 years ago, and I followed him from there throughout his tenure as U.S. Senate majority leader.

I had written columns and editorials about him, and later did periodic interviews on subjects as diverse as the September 11 attacks, Northern Ireland, and the elusive prospects for peace in the Middle East.

Yet I found that, in important ways, I hardly knew him at all. Through dozens of interviews and many months in the library, I looked into his career as an attorney, before he entered politics and then after, when he headed the world’s largest law firm. His behind-the-scenes role in saving Major League Baseball from itself, well before the famous “steroids” report; his rescue of the reputation of the American Red Cross; and his navigation of turbulent waters at the Walt Disney Company were all new to me.

Reading the documents from his early life amid humble surroundings in Waterville, his days as a shy and uncertain Bowdoin College student, and his work with U.S. Army Intelligence in divided Berlin presented new and unexpected aspects. His turn toward politics when he was, almost out of the blue, offered a job on Sen. Ed Muskie’s staff in Washington, showed how major life decisions owe much to fortune and chance—even for someone as determined and disciplined as George Mitchell.

When Mitchell decided to leave the Senate in 1994—stunning many of his strongest supporters—we, and probably he, knew only that he planned to marry again and raise a family, and await opportunities. That his public service would include helping bring peace to Northern Ireland and serving vital missions in the Middle East was of course unknown at the time.

But it was not surprising.

For what is most striking about George Mitchell is that he was able to unite the habits and skills of a lifetime to become perhaps the most extraordinary negotiator of our time—as he fittingly titled his own memoir when it was published last year.

Negotiation is an arcane and sometimes misunderstood art. The skills Mitchell possessed in abundance—the unfeigned willingness and interest in listening to every person who came before him, including every Maine constituent; his extraordinary patience; his ability to maintain his temper amid trying circumstances—all served him well. These qualities enabled him to win the trust of diverse parties and groups, some of whom had been adversaries for decades, and whose disputes went back centuries.

Yet if there is one quality which elevated Mitchell above his peers, it was his willingness to do hard work—the toughest work—that many others shy away from. His years as Senate majority leader are often described as an oasis of bipartisan achievement, against the increasingly stark position-taking that now substitutes for lawmaking in Washington, and many state capitals as well.

Yet his victories on the Clean Air Act, the last bipartisan federal budget agreement, and other monuments of sound public policy were not achieved just through “civility” or “compromise,” important as those qualities undoubtedly are. He spent long hours in committee and in the caucus room, testing ideas, rallying support, employing persuasion and persistence in ensuring that fractious groups of senators finally came together in support of common goals. Since his departure from Washington, there have been no comparable Senate leaders.

Mitchell avoided the blame and derision that often goes hand-in-hand with public office in part because of his innate sense of humility. His friends were often amazed, and his adversaries confounded, by his willingness to share credit for achievements, and even confer credit on others beyond what they thought was their due. It is a disarming, and effective, means of keeping the peace among often towering egos.

As he would be the first to admit, George Mitchell is not without his faults. He made mistakes, and sometimes disappointed others. Yet there is much to learn from his example, and from his continuing public career—lessons that I am still hearing about, and writing down.

Statesman: George Mitchell and the Art of the Possible (Down East Books) is available at bookstores and online. Signed copies are offered at these readings by the author:

Sept. 11 – Maine Irish Heritage Center, Portland, 2 p.m.

Sept. 13 – Bangor Public Library, 6:30 p.m.

Sept. 20 – College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, 4 p.m.

Sept. 22 – Camden Public Library, 7 p.m.

Douglas Rooks is a career journalist, and former editorial editor of the Kennebec Journal, and editor and publisher of Maine Times. This is his first book.