Posted September 27, 2018

Last modified September 27, 2018

By Tom Walsh

If you don’t know much—or even anything at all—about Rachel Carson, here’s your chance.

The Library of America recruited the help of editor Sandra Steingraber in recently publishing a new retrospective on marine biologist Rachel Carson and her seminal role in jump-starting environmentalism in post-World War II America.

Rachel Carson: Silent Spring & Other Writings on the Environment is a 550-page anthology of Carson’s writings and her correspondence with colleagues and friends, prefaced by Sandra Steingraber’s analytical and biographical insights.

Steingraber explores how Carson used research to connect the dots linking cancer-causing impacts of even small doses of radioactive fallout from atmospheric bomb testing and the public health impacts of drifting farm herbicides and pesticides. Carson wondered how small traces of radioactive fallout could find their way into the bones and baby teeth of small children. She wondered, too, about the extent to which farm chemicals were tainting the milk in baby bottles.

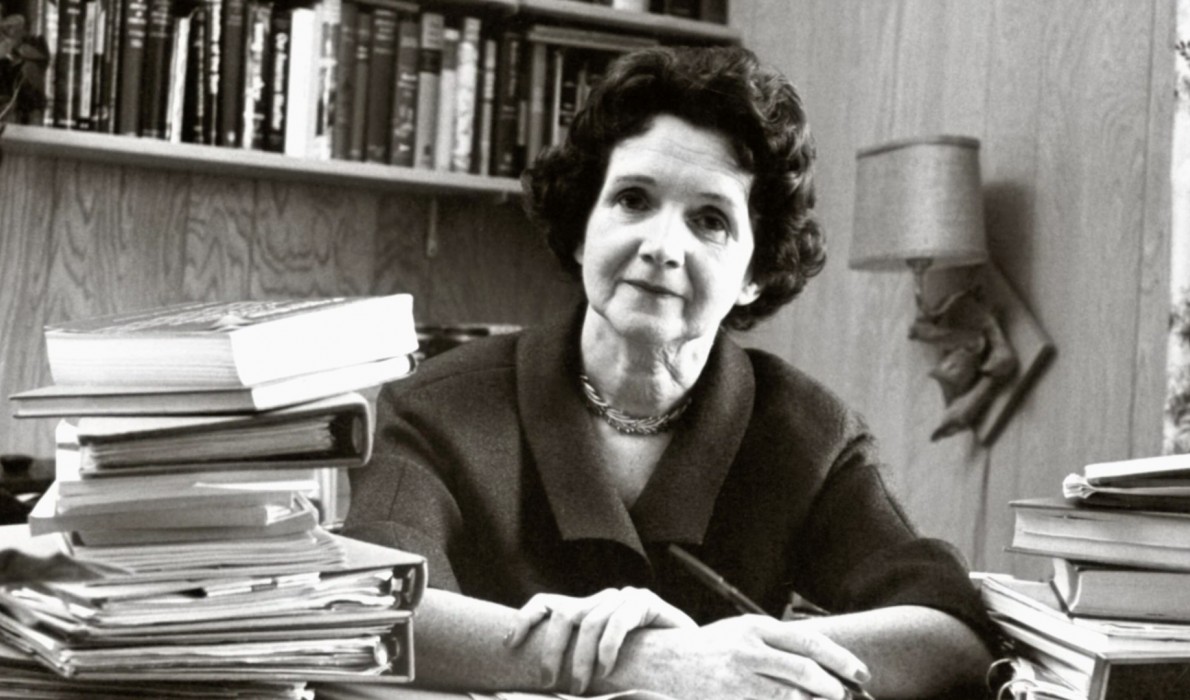

This remarkable woman and her best-seller Silent Spring came out of nowhere as a call to action for what quickly evolved into the foundation of America’s early environmental movement. In 1962, as a largely unknown science writer who was by then editor-in-chief of all U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service publications, Carson’s Silent Spring awakened America and the world to the cancer-causing realities of the spreading use of clearly dangerous and potentially lethal chemical pesticides and herbicides, synthetic compounds she termed “elixirs of death.”

Curiously, she died in the spring of 1964 of complications of breast cancer. Posthumously, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Jimmy Carter.

Carson’s research-heavy exposé of the health hazards of human exposure to pesticides and herbicides through food and drink as ubiquitous as apples and milk quickly became a best-seller and a popular radio and TV talk show topic. Public concern over the book’s call to arms resulted in the highly carcinogenic compound dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) being banned as a pesticide for both agricultural applications and use as a pesticide fog actively embraced by urban America as a chemical deterrent to mosquitoes.

An immediate, well-financed and carefully orchestrated effort to discredit Carson’s extensive research and its dire conclusions was undertaken by the chemical industry, including Monsanto and American Cyanamid, with the active support of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That campaign included a not-to-worry, much-ado-about-nothing report published by National Academy of Sciences, although its authors turned out not to be Academy members. Instead, they were associates of 19 chemical companies and four trade organizations, including the National Agricultural Chemical Association.

Carson once described herself as “a priestess of nature, a devotee of a mystical cult having to do with the laws of the universe, which my critics consider themselves immune to.” Having grown up in an Allegheny River town in Pennsylvania in the early 20thcentury, she split her time after college between her home in suburban Washington, D.C. and her seaside summer retreat in Maine on Lincoln County’s Southport Island.

Drawing on her expertise as a marine biologist, Carson wrote Under the Sea Wind (1941) and The Case of the Sea (1955), both books well received by readers drawn to science. Carson was the founding chairman of The Nature Conservancy’s fourth state chapter, in Maine. The 5,300-acre Rachel Carlson Wildlife Refuge now includes 5,300 acres abutting shorelines between Kittery and Cape Elizabeth.

There was perhaps nothing that touched Carson’s soul more than a walk in the Maine woods: “A rainy day is the perfect time for a walk in the woods,” she wrote in her poetic prose in “Help Your Child to Wonder,” an essay for Woman’s Home Companion magazine in 1956. “The Maine Woods never seem so fresh and alive as in wet weather. Then all the needles on the evergreens wear a sheath of silver; ferns seem to have grown to almost tropical lushness and every leaf has its edging of crystal drops. Strangely colored fungi—mustard-yellow and apricot and scarlet—are pushing out of leaf mold and all the lichens and the mosses have come alive with green and silver freshness.”

As a science writer for many years, it’s not a stretch for me to suggest that Carson’s Silent Spring is arguably among the 20th century’s most significant books. Carson should have been awarded a Nobel Prize, not only for her insights, but for the impact that her insights had globally over many generations. Unfortunately, in the early 1960s, being a bright-off-the-charts woman, a visionary, and a spinster wasn’t in vogue.

Tom Walsh is an author, journalist, and science writer. He earned his master’s degree in science communications from Dublin City University in Ireland in 2002. He now lives on West Bay in Gouldsboro.