Posted May 19, 2020

Last modified May 20, 2020

By Jack Sullivan

I was looking forward to doing something fun to celebrate my home state’s 200th anniversary of statehood. I wanted to have a few friends over and make a toast to the 23rd state of this great nation—maybe even pour one out for Joshua Chamberlain.

Unfortunately, March 15 was the weekend it was no longer medically acceptable to have visitors in your home. It was not a time for celebrating at all. Jobs in Maine and elsewhere suddenly disappeared, and the stock market saw a sharp decline.

Yet, truth be told, it makes perfect sense for Maine to celebrate its 200th anniversary in the midst of uncertainty and economic crisis. Maine has seen booms and busts of epic proportions for as long as it has had a modern economy. These devastating busts and our perseverance in recovery make Maine so special and worth celebrating in the first place.

So instead of celebrating my favorite state with my friends, I found myself practicing social isolation and poring over dusty college text books, specifically my books on Maine history. It was in those books that I was reminded of how often Maine has faced economic turmoil.

The Pine Tree State is exactly what the name implies—a state whose identity and economic vitality depend on nature. Pine lumber is one of many resources that have propelled Maine to economic prosperity, only to see it unceremoniously fizzle and leave Mainers unemployed.

Nature has granted us expansive opportunities, but natural resource economies can be fragile. Competition from away has pushed Maine out of certain natural resource markets. New inventions can cause a resource to become obsolete. Other times, nature stops giving when we’ve taken too much.

Each of these scenarios can—and have—put large numbers of Mainers out of work.

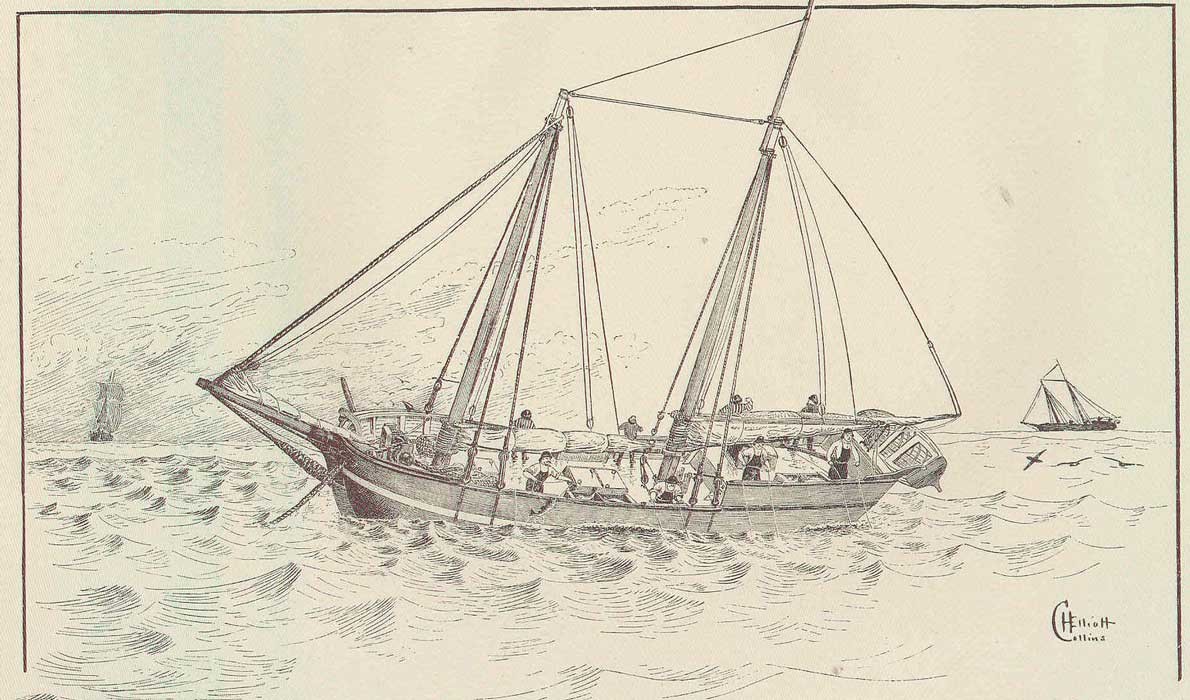

A graph of cod landings from the 1860s to the 1890s shows a sharp downward slope, much like the graph I was looking at earlier that day—that of the Dow Jones Industrial average for March 2020. Mainers have been seeing these sharp declines since statehood.

Around the time of the Civil War, Maine landed 57 percent of all cod tonnage. However, in the late 1860s, a combination of competition from Massachusetts and Newfoundland and inadequate railroad access to Maine ports caused our cod fishery to diminish, putting fishermen out of work and forcing them to adapt.

In this case, adaptation meant carving out a new niche in the marine market. Investors in Maine shifted their focus from coffshore fisheries to the burgeoning lobster industry—a solution that has paid off through today.

This pattern extends to the 20th century in other ill-fated natural resource industries. Ice harvesters became obsolete when artificial refrigeration entered the market. The collapse of that industry and the ensuing loss of jobs had nothing to do with the work ethic of the harvesters or the quality of the product, just like those Mainers currently out of work had no control over the pandemic.

Likewise, in the early 1900s, the rise of steel and concrete in construction took its toll on Maine’s granite industry. Sometimes, as in the case of the 1,500 on Hurricane Island whose lives were tied to the granite industry, people lost their livelihoods suddenly and learned overnight they had to start from scratch.

More recently, Maine has found itself facing steep declines in manufacturing jobs.

“We have seen the rise and fall of textiles, boots and shoes, and pulp and

paper,” writes Stephen J. Hornsby, director of the Canadian-American Center at University of Maine and co-editor of The Historical Atlas of Maine. “All these industries created particular types of settlement—commonly one industry towns—which boomed during the good years and then suffered greatly as their industries closed. We are seeing this right now with the old pulp and paper towns.”

In my own lifetime, I’ve seen mills close, putting substantial portions of a town’s population out of work. I’ve also seen those towns remain vital because of strong leadership, creative problem solving, and unbreakable willpower. Those assets can prove to be far more valuable than tangible resources like lumber, granite, and cod.

In last month’s issue, we examined Biddeford, and how its former mill buildings were being repurposed to catalyze community resurgence—

proof that the innovation needed to overcome such challenges exists here in our state.

Even in the period since the pandemic derailed the economy as we knew it, I’ve seen fishermen improvise by selling their products straight to consumers, bypassing the channels that have been hamstrung by COVID-19. Maine has the resources to survive hardship—it’s not in the industries on which we rely, it’s in our history, our character, and our blood.

Jack Sullivan is a multi-media storyteller with the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

Contributed by