Posted April 13, 2016

Last modified April 13, 2016

“We will be the ancestors someday.”

This truism came from Penobscot Nation tribal elder Butch Phillips as part of the welcome to over 300 people who attended the Penobscot Watershed Conference on April 9. The statement was a weighty one—when future generations look back, what will they learn from the actions we take today?

Phillips’ simple but powerful assertion is increasingly important in a nation bent on immediate gratification. It places each of us on a continuum that is difficult for humans to contemplate, a timescale of thousands of years.

Should we dredge or not? What about siting a shellfish farm? Should we preserve more open space, with or without public access? How will our ancestors judge our actions?

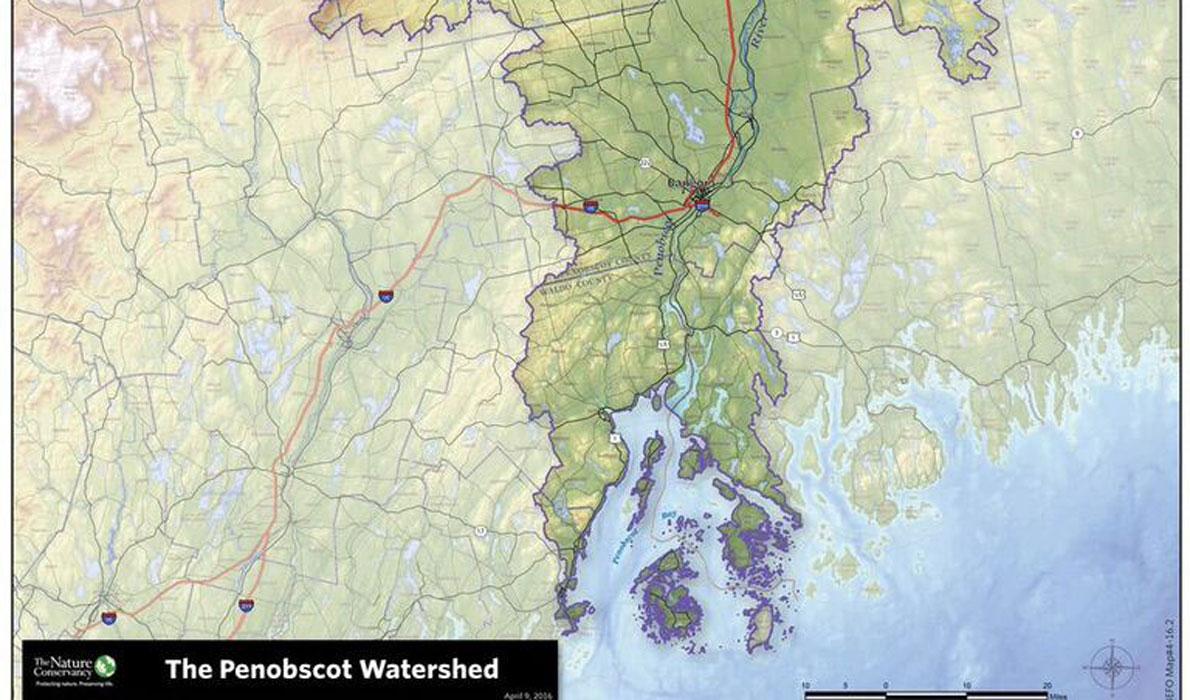

It’s fitting that these questions arise from the view of the people who have been driven from much of their ancestral land. And yet, when looking at the Penobscot River and Bay—the entire watershed—the Penobscot Nation clearly remains central.

Presentations throughout the conference revealed centuries of industrial uses in the bay. Dr. Bob Steneck of the University of Maine showed a map depicting the high density of fish weirs in the upper bay in the 1800s; a fish would have to be brilliant to get past them and into the Penobscot River. Steneck compared the damming of the watershed to a human circulatory system with clogged arteries, suggesting that both were life threatening. In other words, it shouldn’t be surprising that the fish are gone.

In fact, be it timber, granite or fish, it was evident that ever since Europeans arrived, our primary access to the global economy has come through some form of resource extraction. Today along the coast our lobsters connect us to the global economy. As with timber and granite, we have learned that global connections based on a single commodity are tenuous at best, and can be disastrous for community economies.

While our economic past was on display at the conference, our future economy remained somewhat unclear. There were a few notable rays of light. Carl Wilson of the Maine Department of Marine Resources sees significant potential in the near-shore scallop fishery. New, intensive area-management measures appear to be rebuilding that fishery, but it is still too early to know what role it might play in our community economies.

Dave Gelinas of the Penobscot Bay and River Pilots Association painted a picture of energy transport that clearly linked our port infrastructure to energy markets throughout the region. As more renewable energy sources come on line it’s clear that rail infrastructure will be increasingly critical to meet future clean energy needs.

The work to restore the Penobscot River system through dam removal highlighted efforts to restore fish habitat, with the hopes of meeting the future food needs of native peoples, supporting tourism and at the ecosystem scale, supporting commercial fisheries in outer Penobscot Bay.

I had the pleasure of moderating a panel on the future workforce in the bay. Our discussion covered the importance of boat building, aquaculture and transportation as critical aspects of our future. But where will the workforce come from? Dana Morse of Maine Sea Grant spoke of the importance of helping lobstermen enter the aquaculture industry. In addition to considering how to support fishermen as they diversify their incomes, the panel focused on the importance of working with school-age youth. The group recognized that perhaps the most important skill our children will need as they move to careers throughout the watershed are communication skills.

Todd West, principal at Deer Isle-Stonington High School, talked about the importance of teaching kids to be effective at the table with decision makers.

Implicit here is a recognition that future uses of the Penobscot watershed will always be debated. Year-in and year-out, I see tremendous energy spent debating what type of communities we are becoming. How will we balance tourism with the growth of the aquaculture industry and how will new ocean uses relate to the current king of the coastal fisheries economy, lobster? The watershed conference made it clear that our coastal communities have much to learn from forestry dependent communities that have seen cycles of boom and bust.

Questions of the future feel urgent, they feel immediate, and in fact they are for so many people who make their living throughout the watershed. Yet, as Member of Congress Chellie Pingree noted in her opening comments, “Change is coming quickly.” How will we deal with change?

Can we take up the Penobscot Nation’s challenge to answer questions of change with the perspective of a people who have been here for nearly 10,000 years? Yes, but it requires a long view on the matter.

I close by repeating Butch Phillips’ opening insight: “We will all be ancestors some day. Will we be worthy of their prayers for guidance?”

Rob Snyder is president of the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. Follow Rob on Twitter @ProOutsider.

Contributed by